Home for the Holidaze: MAC Planes, Duty Trains and Channel Ferries

The Metronome of Falling Rain

It’s gray, cold and raining outside - a typical winter day in Seattle. The metronome of falling rain and the splashing puddles in the street recall holidays past and winter term breaks when the college campus was empty, the dormitories vacant and home many many miles away.

Most people I knew at university grew up only a few hours drive from where they went to college. I, and others like me, however, came from thousands, often several thousands of miles away. Some of the international students’ homes were even more distant than mine. For us, the short Christmas term break was a problem. It was too long to just wait it out in academia’s winter ghost towns and too short to book an expensive flight half way around the world.

I was, in those days, what they called an Army brat. As a brat, there was an alternative. I could catch a free flight, assuming there was space available, on a Military Air Command flight (”MAC”) to wherever they were flying. Because the U.S. military has more than 700 bases around the world (not counting the secret ones), there were always MAC flights heading wherever. Some of them were not part of clandestine operations. Others were. The problem was timing and the availability of (non-clandestine) seating. With a little luck and a lot of perseverance, I might get close enough, quickly enough to get home and back again before classes resumed next term. Or I might get air-dropped into an implausibly deniable “hot zone” somewhere never to be seen or heard from again.

It was the holiday season, 1974. The Vietnam War was still dragging on even though many U.S. troops had been withdrawn. Richard Nixon had resigned from office and Gerald Ford was President. I looked like a hybrid of Frank Zappa, Che Guevara and Karl Marx. A gallon of gas cost 53¢ at the pump. The Treasury Department still minted pennies. There was no Internet, no cell phones, no home computers, no spam, no email. There was no artificial intelligence. Perhaps there was no intelligence. Japan had not yet declared its intention to rearm and build nuclear weapons. Germany had not yet declared its intention to rearm and attack Russia. Again. No one campaigned to make America thuggish again. John F. Kennedy had already been assassinated. Likewise Robert F. Kennedy. And Martin Luther King. And Malcolm X. And Black Panther Fred Hampton.

John Lennon would die a few years later.

“Give Peace a Chance,” we sang.

My initial problem was getting to McGuire Air Force Base near Fort Dix in central New Jersey. From where I was, smack dab in the middle of Pennsylvania, getting to McGuire AFB was a simple matter of taking the Dog - one of the Greyhound Buses that crisscrossed the state - east to Philly, and then transferring to another bus to Trenton, and then taking a Trenton city bus to McGuire AFB. That alone took a full day riding through back-country snow and brown city slush. I’m not sure that I would hazard that exact itinerary today, traveling mostly by night. But that was then, roughly 50 years ago, and I did. I think, by my appearance alone, I probably frightened more people at the transit stations than there were people who frightened me.

Once I arrived at the passenger terminal of McGuire AFB, I had to sign in; confirm my identity; prove that I wasn’t Frank Zappa, Che Guevara or Karl Marx; register my ultimate destination (West Berlin, Germany); and then... wait.

And wait.

And wait.

The routine for flying MAC “space A“ (as flying “space available” was called) was that you had to be there, in person, ready at a moment’s notice to hop on a plane.

Your name was announced over the public address system. You had ten minutes to acknowledge the page and get aboard. You snooze, you lose. If you had spent the night at a motel, you would have missed your flight. There were no second chances.

I recall that December that I was among about a hundred students trying to get home for the holidays. Most of us were trying to get to Europe somewhere - Germany, England, Belgium, or Italy. Others were heading to Turkey, Greece and anywhere else where the Empire stationed its legionnaires. I imagine that other students heading to Okinawa, the Philippines, Guam or Korea for the holidays would have been directed to muster at a MAC air base somewhere on the West Coast.

December 22nd. A seat opened up on a cargo flight to Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and someone took it.

The next day, December 23rd, several others caught a transport plane to Rome.

That evening, there was space on a flight for one or two students heading home to their families in Tehran. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was still half a decade away. America’s satrap, the Shah, put in place in 1953 by a US-UK coup, still ruled the country and sold its oil at discounted prices to western petroleum companies. The Shah ruled, with U.S. and British assistance, with an iron fist, absolute power and a regime of torture and terror. I think this might be the kind of thing that Mr. Trump has in mind when he wants to make America “great” again.

By morning December 24th, there were still a lot of us hanging out in the waiting lounge. We had all been sleeping on the floor, heads resting on our backpacks, wrapped in our winter coats beneath the overhead fluorescent tube lights. We were like clochards in Paris hanging out under the bridges. We couldn’t leave because we might miss the call. After two days we were incredibly bored and we all needed to shower.

To pass the time, I organized a chess tournament. We took different size soda and coffee cups from the snack bar and fashioned them into playing pieces. The jumbo size paper cup was the King. The mid-size cup with a straw sticking out of the lid was the Queen. Styrofoam coffee cups were Bishops or Knights. Napkin dispensers were Rooks. Packages of ketchup were our Pawns. The playing board was the floor itself. This was a standard U.S. military floor comprised of vinyl squares of two nondescript colors: sort of brown and sort of beige. Every American military base has floors like this. Fifty years later, the floor of the waiting lounge of McGuire AFB probably still looks the same.

Anyway. For us, the checkerboard vinyl floor became our chess board. We set up at least two simultaneous games using the cups, straws and plastic lids. We took over almost the entire snack bar, moving tables and chairs off to the side. The military police came by and watched us play for hours on end. Because we - and the MPs - were bored. Finally, some officer somewhere decided that all this game-playing on the parquet floor was an unacceptable breach of discipline and a bad example for the soldiers. Maybe they thought the troops would mutiny if they saw us playing chess. Probably so. So they shut down our chess games and made us push back the tables and chairs.

It was now Christmas morning. A lot of us were still stuck at McGuire Air Force Base. Most were heading to somewhere in central Europe. The weather was bad. It would have been difficult to return to our various depopulated college campuses. But it also looked like, instead of being Home for the Holidays, we would spend the Holidays sleeping on the cold, hard floor of an air force base.

There was a rumor, just a rumor, that every year, when all other “space A” flights failed, that there would be a miracle, the Santa Express would appear. And then it did. Late in the afternoon of the 25th of December, the public address system announced a “training flight” was heading out to Europe with enough seats for everyone in the waiting area who wanted to go.

I went.

I think it was a C-5 Galaxy. It had a cavernous interior equipped with web seats made of orange plastic designed to accommodate several hundred soldiers in battle gear. The interior of the plane was stuffed with a medley of crates, tracked and wheeled vehicles, and other unidentified stuff in boxes and barrels, possibly ammunition or nuclear warheads, who knows. All of our backpacks were also piled in the middle of the plane covered with a tarp and tie-downs. There was no in-flight movie. It was cold and very noisy. But it was free. We were headed to Europe on the Santa Express, heading home for the holidays. Wherever we were going was where we were going. After I got to wherever we were going I would worry about the next leg of the trip. When you fly “space A” you go wherever the flight takes you. And so it was.

A few hours into the flight, a young uniformed Airman First Class came by distributing plastic wrapped ham and American cheese sandwiches on Wonder Bread, bags of potato chips and soda pop. Airman First Class was the Air Force equivalent of a private. Actually, he didn’t so much as distribute sandwiches as toss them at us. I remember that he was hostile towards all of us students. I didn’t understand why at the time, but the impression stayed with me for so many decades that he really disliked us. The Airman was Black. Most of us students were White. Most, but not all.

Now, I understand the hostility, but then I did not. He could have been a “volunteer” who had joined the Air Force to avoid getting drafted. At that time, I believe, conscripts served two years in uniform. The Army mostly needed “grunts” to serve in the field, to shoot and to get shot at. Or, you could enlist, serve three or maybe four years instead of two, but have some degree of choice in what branch of the military you served.

Was this particular Airman a draftee - or a “volunteer” trying to avoid the draft? We clearly were not draftees. We were going to college. He clearly was not. We were flying home for free for the holidays. He had been ordered to help fly us home free for the holidays. The “Santa Express” was a crappy assignment for him. So as we - the privileged dependents of officers and Department of Defense civilians - were flying home for Christmas, he was flying away from his home for Christmas. Fifty years later, I figured it out. It wasn’t a matter of race. It was a class thing. Intuitively, he knew it. We didn’t. No wonder the soldier didn’t like us. I’m surprised he didn’t poison the ham and cheese sandwiches with jet fuel. Maybe he did because it tasted awful. But all mess hall food tastes awful, so whatever.

We landed early in the morning of December 26th at the U.S. Air Force Base at Mildenhall, England. Several U.S. B-52 bombers were parked on the tarmac. We deplaned and looked around. It was “Boxing Day” in England. Everything was closed. Transportation was minimal. Almost everyone living nearby was “home for the holidays.” Several of us wanted to get to the Continent. I was trying to get to Frankfurt where I could catch the U.S. Military Duty Train to Berlin. The problem was to get from Mildenhall AFB in Great Britain to central Germany, sort of the reverse of what Germany sought to do in 1940.

My memory fails me on this point. I think I ate some kind of sausage in a bun at the local train station. It made the plastic wrapped Air Force ham and American cheese on Wonder Bread sandwich taste good by comparison. Maybe I had a warm beer. Or maybe it was lukewarm coffee. I don’t really remember. Perhaps someone else who rode with me on the 1974 Santa Express will read this story and write to fill in the gap. All I remember is, maybe, traveling by railroad to somewhere near London and thence to the coast. There was no Channel Chunnel back then. They were still afraid of Napoleon crossing the Channel and invading from France, I think. I might have taken a train that was loaded onto a ferry and then floated across to the mainland. It was a rough sailing. The ferry docked and disgorged the train. It then zigzagged here and there arriving, eventually, at the Hauptbahnhof in Frankfurt, Germany.

Our band of student travelers had largely dispersed by this time to various towns and cities across Central Europe. I might have been the only one now still traveling east. I checked in to the U.S. Military dispatch station at the Frankfurt train station and picked up my “flag orders.” Then I waited, again, for the train to West Berlin.

You needed “flag orders” to get into West Berlin because the Cold War was still a thing back then. The Soviet Union had not yet collapsed. There was West Germany, the BRD (Bundesrepublik Deutschland), and there was East Germany, the DDR (Deutsche Demokratische Republik). It was rather like North and South Korea then and now. Or North and South Vietnam. All were vestiges of the Second World War which was just an episode in The Second Hundred Years War that began in 1914 and continues without interruption today. West Berlin, in 1974, was smack dab in the middle of the DDR, itself an “occupied city” partitioned since 1945 into four “sectors” run by the U.K., France, the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The “flag orders” permitted the holder to travel by military train across the DDR to West Berlin.

You could also fly to Berlin, but only three commercial airlines were allowed: Pan Am, British Airlines and Air France. No civilian German flights were permitted in the air space over Berlin. We could drive, too, from Helmstedt to Berlin by car taking a 170 kilometer course along a poorly maintained highway past Soviet and DDR checkpoints. But the rules were so onerous and the armed soldiers on both sides so twitchy that it was an automotive trip I undertook only once in my life. Did I once, en route, trade something at one of the Soviet checkpoints, perhaps a Playboy Magazine or a pair of Levi’s in exchange for a DDR flag? I do have that DDR flag somewhere, with its socialist logo of a protractor and an industrial mallet surrounded by sheaths of wheat. Perhaps I traded a pair of old Levi’s for it.

Anyway. There I was stuck at the Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof. I was eating more plastic-wrapped ham and American cheese sandwiches on Wonder Bread sold from the vending machines. Nobody knew anything about “organic” food in those days. The vinyl parquet floor of the train station waiting room looked exactly like the floor of the waiting area at McGuire AFB in New Jersey. I was bored and tired. I walked around the train station killing time. It was getting on toward the evening of December 26th. Or was it already the 27th?

All central European train stations look and smell pretty much the same. They are all dark and cold and damp and smell a little like urine and disinfectant. That’s because, at that time, all the train toilets flushed directly onto the tracks. Passengers weren’t supposed to use the head when the trains were in the station, but they did anyway. The public address systems in Europe’s train stations were also uniformly garbled:

Ding Dong! Mmmenn ooplsgryu bra Bbbbschtatgivnawhatevrd!! GLABBA BLABBA!! Nuuh, Stadt ‘nberg uberradahah ‘ankfurthgarashnebuk Nuztch na bblumer blummer blummer Nummer nnnnnenkjnknjelkfne ojoi0 und 876 blah blah blah. Nyah nukka nmmmlikkkddfjk.... Ding Dong!

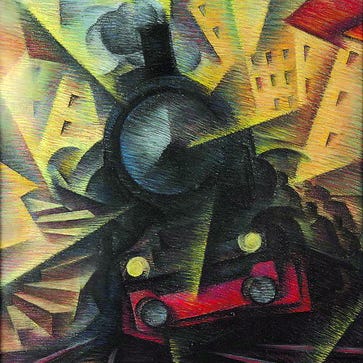

The Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof is big. It was mildly entertaining to walk up and down the platforms watching the human theater of missed trains, passengers running to find the right departure track, families meeting long lost relatives, friends shaking hands, people crying, hand carts full of luggage not yet loaded on trains, people waving goodbye, couples kissing, porters driving small baggage trains to load onto full-size trains, bells clanging, steam steaming, steel wheels grinding on steel tracks. Things going bump and bang and grating metal on metal.

I boarded the American military duty train. It only ran at night from Frankfurt to Berlin. It was a spartan kind of transport: six bunks to a room. Once the train departed, you were supposed to lie down and sleep until you arrived the next day at six in the morning. There was no dining car. There were zero amenities. The train was patrolled by armed military police.

That is to say the American military duty train was a spartan kind of transportation. The British had their own Duty Train that ran in the afternoon in and out of Berlin. The Brits provided tea in a dining car, of course, served by waiters in white jackets. The British Duty Train was patrolled by burly Scots Guards wearing kilts with long knives tucked into their stockings. The French Military Duty Train was an altogether different thing. It ran overnight from the French Sector of Berlin to Strasbourg. The French Duty Train had private compartments for two equipped with white linen and bidets. You could order a bottle of wine or cognac. They had room service. In the morning, they served continental breakfast in your train compartment. There were no guards at all on the French Military Duty Train. Or, if there were, they were disguised as waiters. The waiters all looked like Peter Sellers as Inspector Jacques Clouseau in a Pink Panther movie.

But I was riding the American Military Duty Train. It was the night of December 26th. Or was it the 27th?

I can remember every detail about riding the Duty Train because I must have taken it more than twenty times in the years I lived as a teenager in West Berlin. The six-person couchettes were stacked from floor to ceiling, three narrow bunks on each side. Temperature control was non-existent. The rooms were too warm or too cold. There was no in-between. Getting into or out of your bunk inevitably involved getting stepped on or stepping on someone else. Invariably, one (or two or three) people snored. Loudly.

I can, even today, vividly recall the sound of the train wheels on the tracks, the rackety-clack of the rails, the whoosh of tunnels and overpasses and passing trains rushing in the opposite direction on adjacent tracks, the dinging of bells at cross-roads, the locomotive’s horn sounding a warning for something or other, lights of small town stations as we whizzed by, the clatter of steel bogies rolling through the switches. The train speeding up. The train slowing down. The train starting. The train stopping. The train starting up again. Clatter. Bump. Whistle. Clang. Bump again. I hear it all as vividly as if it was yesterday.

Part of the game in those Cold War days was to make life miserable for one another. I now understand that all of it was perfectly ridiculous. The “drama” was intended to make all of us feel “threatened” by the “Enemy.” In fact, the “Enemy” was actually the leaders of our own nation states, not the young and impressionable soldiers who carried out their dirty work. But that was then, when we were all young and stupid. Now, though still stupid, we are no longer young.

Thus from Frankfurt to the border crossing from the BRD to the DDR, our train was pulled by a diesel-electric locomotive. At the border, the guards noted from the “flag orders” and the passenger manifest who was on board. They recorded their names, ranks and identification numbers. Later, they probably tossed all this useless information into the burn box. Today, our personal data gleaned from the passenger manifest would, instead, be sold to Google, Oracle, Meta, Palantir, Microsoft, or X. They, in turn, would sell it to spammers and various folks who collect data on you and “curate” advertising for your digital devices. Thus are the spoils for the victors of the Cold War. Anyway. The “West German” locomotive was replaced for the trip through the DDR. Instead of a diesel-electric, our train was then pulled by an old coal burning steam engine. The smoke was intended to permeate the compartments, and it did. But, for me, even the smokey old steam engine was part of the charm, even if its intention was malicious.

The DDR/Soviet locomotives sounded different from the western diesel-electrics. I barely dozed through it all because I listened to every sound in the night. That, plus all the snoring. And then, when we approached Berlin, they changed locomotives again, because the DDR engines weren’t allowed into the West Sector of the City any more than the West’s engines were allowed into the DDR. Pure theater, of course, but it continued unabated until 1989. Now, we still have the Cold War Good Guy/Bad Guy theater, but it’s moved further east.

One other sound I recall from that trip heading Home for the Holidays on the American Duty Train. I heard this sound and remember it from every one of the twenty or so trips I ever took on that train during the years I lived in West Berlin. It is the sound of the conductor walking down the aisle, rapping a brass key on the glass aisle windows of the compartments, announcing the arrival at the station in 30 minutes.

Rap rap. Rap rap. Rap rap. Rap rap.

I could hear the conductor walking down the corridor and rapping a key on every compartment’s glass window, coming closer and closer.

Rap rap. Rap rap. Rap rap. Rap rap.

I was wide awake by the time he got to my compartment, but by then I was almost too tired to get up. But I had to, because several hundred people would now pile out of their bunks in the long line of sleeper cars to line up at the lavs and to wash up in the rows of sinks, shaving, brushing teeth, getting dressed.

So I arrived, bleary-eyed, that morning of December 27, 1974, at 6 a.m. Or was it December 28th? I was home for the holidays.

It was gray, cold and raining outside. The metronome of falling rain and the splashing puddles in the street reminded me of the empty dormitories of the college campus I had just left. There was brown slush in the gutters, just like the other side of the Atlantic.

It took a while to acclimate myself to “home.” I had aged and, to my surprise, so had my parents. They had their old habits and I was developing new and different ones. Everything looked the same and yet it was all somehow different. We were growing apart. I no longer felt quite at home while at home.

A few days at home were all I needed to remember why, in the first place, I had left home to go to school so far away from home. Memories are nice, but they get tangled in cobwebs. Memories need to remain memories. They cannot, and ought not be relived.

New Year’s Day was approaching. Because the outward bound trip had taken so long, it was already time to go back. So I did it all again in reverse.

The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig wrote Die Welt von Gestern, (”The World of Yesterday”), his reminiscences of the peak cultural years, and the decline, of Vienna, the capital city of the Hapsburg Empire. His Vienna was the time of Gustav Klimt’s highly ornamented paintings, Gustav Mahler, light opera, philosophy, mathematics, literature, high fashion, music, theater and Sigmund Freud. The world then, like now, was changing fast, and not for the better. Stefan Zweig fled Austria and the Nazis for exile in Brazil. Those were unstable, turbulent times, like now. Zweig finished writing the manuscript for his book in 1942 and then sent it off to his publisher. Then he committed suicide.

I’ve read Die Welt von Gestern both in English and in the original German. It’s not my favorite book. Rather like Marcel Proust or F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mr. Zweig was enchanted with the superficial baubles of high society. It was a fine life, indeed, for a small class of people who lived in a fairyland. The fairyland collapsed as World War erupted again and Mr. Zweig was unable to survive the collapse of the only culture he could live in.

I do not tell stories from my past or yours just to romp down memory lane. Everyone has stories. Usually, the smaller stories of ordinary people are much more interesting than the big stories of big people. It’s a cultural thing. Story-telling is how all peoples throughout time have validated their existence. One generation recites to the next generation what happened, and by doing so, you confirm that something happened. If the story isn’t told, then it might never have happened. If the story is repeated - even if the names and places get mangled in the repetition - then whatever happened becomes real. At least for as long as the story gets told and there are people to tell it. It’s the ‘why’ part of the story that is important, not so much the ‘what’ part.

More importantly, the recollections of the past teach us something about the present and about ourselves. History is not just one damn thing after another. It turns like a corkscrew and, although things seem similar, we never truly end up where we started.

I am at a different home now for the holidays. Some things have changed; some things have not. It’s still wet outside and the metronome of falling rain and the brown slush and splashing puddles in the street remind me of MAC planes, Duty Trains and Channel Ferries.

* * * * *

I truly enjoyed reading this story. Brought back a lot of memories of Berlin and the duty train. Love an adventure and there were plenty of them for us BRATS!