"This isn't my report!" Frank Kelsey protested. He leaned back and widely displayed at shoulder height his open hands in the universal gesture of defiant incomprehension.

Were a pinhole camera focused on the scene... and it is certain that there was... the movie scene would have appeared to be static:

Dr. Kelsy in his short-sleeve blue shirt, looked through the lower half of his bifocals. His posture and his face showed surprise and indignation. He was seated in the low hard guest chair in front of Dr. William Merrell's mahogany desk, the low hard chair intended to make a visitor feel small and uncomfortable.

Dr. Merrell leaned slightly forward in his executive leather chair. Behind him was a credenza. On the credenza stood a careful arrangement of portraits of his wife and children. Dr. Merrell’s hands lay on his desk, his fingers and thumbs touching thoughtfully, his eyes contemplating his fingers. Behind him, framed pictures hung on the walls: university diplomas; photos of various Very Important People standing shoulder to shoulder or shaking hands with Dr. Merrell; civic awards for this, that or the other; pictures of rockets rocketing off and capsules landing. Through the plate glass window in the far wall one could see the manicured grounds, the guarded front gate, the flag hanging limply in the traffic island that separated entering and exiting vehicles.

There, on Dr. Merrell's desk, was the two hundred seventy-five page lunar water report, stamped "Secret and Confidential," ostensibly drafted by Dr. Frank Kelsey, Team Leader, et. al., Project Jump the Moon, lying on the dark wood desk straddling the no man's land between the Executive Director and his subordinate.

The scene remained static. They didn't move for nearly half a minute.

Finally, Dr. Merrell spoke. "Frank, you and I go back together a long time," he said in that ersatz friendly tone the superior uses to address an inferior. "I know this project is important to you. But you also know that it's a lot bigger and a lot more important than either one of us."

Dr. Merrell put up his hand to preemptively stifle the outrage about to burst from Dr. Kelsey's mouth. "Frank, we've talked about this many times before and I know where you are coming from. I respect your opinions. You know I do. But there are times when it is more important to be part of the team than just a stubborn old man who refuses to be reasonable."

The outrage erupted anyway. "Bill, what are you asking me do to? Do you want me to lie? You saw the studies, Bill, the same ones I saw!"

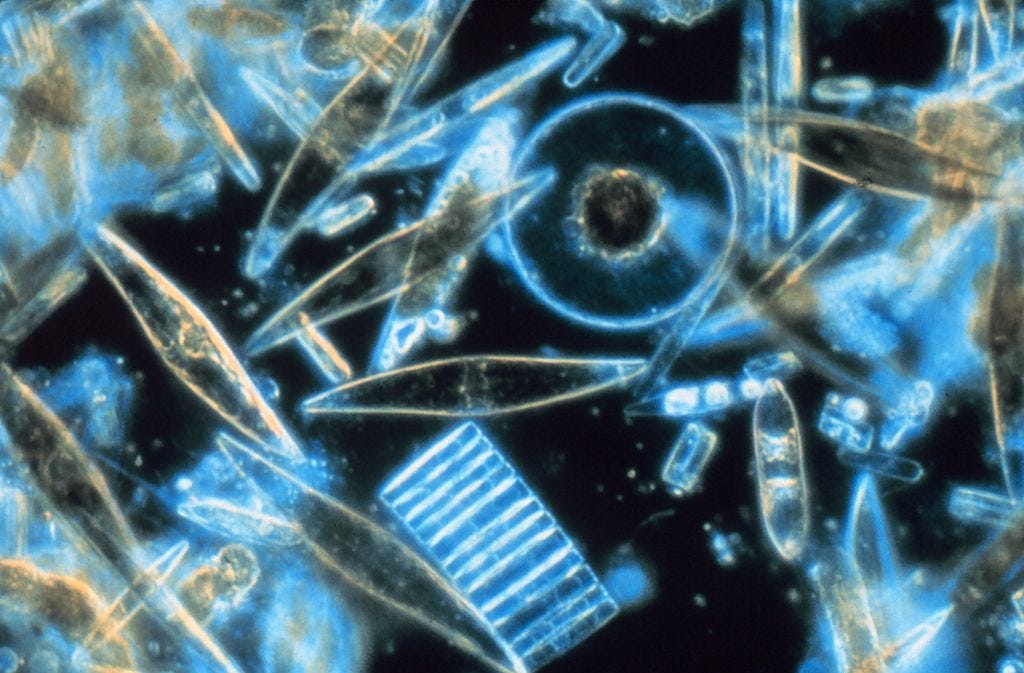

Dr. Kelsey grabbed the report and riffled the pages looking for the pictures of the magnified water samples sent back by the lunar rover inside the newly explored lunar south pole craters. "Look at them Bill! They're unique! We've never seen anything like this before! They're small, tardigrade size, and they must have incredibly slow metabolism--but they're definitely alive, Bill, and they're positively, absolutely not Earth contaminants! This report is 180 degrees opposite from what I actually wrote. This is all bullshit! I can't believe what you are trying to get me to say! Look at the organic analysis, would you already!?"

"Frank. You're wrong. No one agrees with you. Your entire team has already signed off on the report as submitted!"

"That's because you pressured them!"

"No, Frank, it's because they have more sense than you do!"

Dr. Merrell leaned forward, his fingers now interlocked tightly, his eyes drilling into Dr. Kelsey's eyes. He spoke clearly. Softly. Authoritatively. In the tone a superior uses to address a subordinate.

"Frank, you need to listen to me. Project Jump the Moon needs the water we've discovered. The plan was agreed on almost a decade ago: we land on the Moon and we set up a way-station at the south pole. The lunar south pole has water and it is always in the light of the sun. Cheap energy and water - the essentials of space exploration. The Moon becomes a type of service station for the missions to Mars, to Europa, to Titan, to Ganymede, Uranus and beyond. We use solar cells to power the Moon station. We mine the frozen lakes of water on the surface and below the surface of the moon, use some for consumption so we aren't always bathing in and drinking our own recycled piss. And we split most of the rest of the lunar water molecules into their constituent atoms to make hydrogen fuel for the rockets and to provide oxygen for the colonists to breathe. We can't transport all of the necessary hydrogen and oxygen from Earth. It just can't be done. This is the only way to go, Frank. It works because there is no life on the Moon. Not now, not ever! There are just contaminants from prior Earth exploration and it is absolutely imperative that those contaminants be sterilized so that we are not further polluting space with our garbage!"

Dr. Kelsey blew up. "You're wrong! Those samples show nothing like life on Earth! These things have unique amino acids and proteins, a reproductive cycle like no other, a locomotive system - a slow one, no doubt, but by every definition, Bill, they're alive! We don't know anything about them, how they got there, what they live on, what their life cycle is, whether they're connected to anything else. Good Lord, Bill, this is the Holy Grail of space exploration! And now we're going to kill God knows what--we don't even know what we've found--just so we can beat the Russians or the Chinese or the Indians or the Japanese? We're going to do this just to set up some stupid missile bases and mine minerals on the outer planets and moons? We're going to do this just for the Power and the Money? Come on, Bill! I'm not stupid! The chlorination, irradiation and extreme heat decontamination treatment proposed by this report for the lunar south polar water isn't about any environmental concern for humans polluting space. That's pure bull! It's an extermination project. It's genocide on a trans-human scale. It's about more of what humans have always done - lie, cheat, steal, colonize. Always in the name of what's good and always for the sake of exploitation and domination."

Dr. Merrell leaned back in his executive chair and folded his hands behind his head. He was framed by the view through the picture window of the manicured grounds, the flag and the sentry gate.

"Frank. This is a very big deal. There's a lot riding on this--a lot of time and energy has been invested in this and a lot of important people have made it very clear that the project must go forward, full speed ahead. I mean really important people, Frank. The sterilization equipment is already being prepared in situ. You recognize as well as I do that if there really were 'life' on the Moon--and everyone one of us except you, Frank, agrees that there is not--then we can't use the water to hopscotch our way to the outer planets. It will be like some picayune non-viable endangered species, a trifling snail darter, blocking progress all over again, just so starry-eyed idealists like you, Frank, can study these worthless things. And for what? For the sake of pure science? The so-called pursuit of 'knowledge?'

"Give me a break, Frank!!

"We aren't children and we live in the real world. The Universe is Nature and Nature is not some Disney World of eternally happy animations. Nature is not a children's cartoon. It's competitive. It's impartial and it's indifferent. Life is made to be aggressive. Humans, of all creatures, excel at that competitive aggression that Nature demands of its survivors. We are also part of Nature, Frank. Space exploration is in our genes. The cleanup project is going to happen whether you approve of it or not. Space exploration and, yes, even exploitation, is our national and our human destiny.

"And Frank, mark my words: this is the kind of thing that makes a career... or breaks it. We are going to decontaminate what the team correctly concluded we have mistakenly contaminated with Earth's bacteria and parasitic hitch-hikers. We have agreed--that is, all of us except for you, Frank--we have all agreed that we need to clean up the mess we must have accidentally made on the Moon so our Earthly contaminants do not get transported to all the other planets we are traveling to. And if we find Earth contaminants on the planets, too, then we will sterilize and decontaminate whatever we find wherever we find it. Everyone else on the project agrees that this isn't a cover-up, Frank, and it isn't anything ignoble. It's the only responsible thing to do. This is a huge forward leap for humankind, Frank. This is the dream of breaking free from Earth's chains. You can be part of the team. Or...you can be off the team."

Dr. Merrell leaned further forward. "Frank. The time for discussion is over. Are you with all of us, or not?"

Dr. Merrell lifted his hand to again stifle another eruption of outrage. "Look, Frank. Listen to me. You've got responsibilities. You've got a wife. You've got family. You've got kids. College isn't cheap, you know. You have a reputation that--at least up till now--has been exemplary. Why do you want to risk everything, ruin your whole life and your family's, for the sake of...what...some useless, obviously unintelligent dead-end...and, ultimately, unproven alien life form...in some hypothetical evolutionary scheme nobody recognizes, when it's just you, just your ipse dixit, Frank, that these are not just inadvertent contaminates from early Earth exploration?

"Frank! Sign the report! Please! Everyone wants you on board. We need you."

He pushed the confidential Jump the Moon project report across his desk toward Dr. Kelsey.

Dr. Kelsey sucked in air and shook. "No!" he finally shouted and swept the report off Dr. Merrell's desk onto the floor. He got up and left, slamming the office door behind him.

* * *

Dr. Merrell picked the report off the floor and straightened it. For several minutes, he sat quietly looking at the photographs hanging on his wall.

His back-line on the secure desk phone rang.

He pushed the blinking red button and took it hands-free.

"So he won't sign," asked--or rather, stated--the caller, because the caller surreptitiously had listened to the whole conversation and watched it through the live pinhole camera feed.

"No." Dr. Merrell began absently to thumb back cuticle from the lunulae of his fingers. "But I know Frank Kelsey. "He's going to do something rash, you know. He's going to go to the press or write some letters to the academic journals. He does have a good reputation, even though he's wrong."

"He had a good reputation," said the voice coolly. "There are things we know about him. Foolish little things he's done and probably not entirely forgotten. We're all like that, of course. When people are young they do things. You, especially, understand, Dr. Merrell. A person does petty and embarrassing things, but not so petty that they won't jeopardize someone's security clearance."

The voice on the phone paused to let the thought seep in, and then continued.

"And there are bigger and smaller transgressions that one may be accused of, some of which may actually be true. You know, things like past correspondence and friendships with foreign nationals, occasional moral indiscretions, peculiar web searches, certain louche photographs found on someone's computer hard drive, a questionable business expense, a mistake on a tax return that may not have been unintentional, an ambiguous email once sent that now needs to be reevaluated, maybe some ethical transgressions that violate federal laws that no one knows exist. It can all be very public, very scandalous, very dishonorable and very expensive. One learns quickly just how expensive.

“The press and the professional journal editors also know that they should contact us immediately if Frank Kelsey... or anyone else, for that matter... tries to publish something critical about the program. We are satisfied that their own counselors and advisors will confirm that Dr. Kelsey, and anyone like him, is a crank, a charlatan or a tool--wittingly or not--of some hostile power. Maybe it was mental illness or a loner mentality. Maybe it's just something in the water where someone grows up. Frank Kelsey is about to become, in a sense, radioactive.

“No publisher will want to touch him or anyone like him. In a worst case scenario, one could have a car accident. Or the spouse and family could have an accident. People become depressed. Sometimes, out of shame or desperation, stories end like that. And although none of those things need actually come to pass, if they do, they could have a salutary effect on the team effort. Nothing builds cohesion like the group sense of loss for a fallen star."

Dr. Merrell looked abstractly out the picture window. "He does have his own files and research and a copy of the studies of the lunar water analysis. I am sure he uploaded and copied his records."

"Once, he did have his own files and research and copies of the studies," said the voice. We researched Frank Kelsey pretty thoroughly. This meeting was your idea, Dr. Merrell, but we correctly anticipated how it would go. Dr. Kelsey's records are no more. Digital records can be modified and they can disappear quickly and absolutely when one has the tools and access. We did leave a few items in his folders, however, but they've been, what should we say, updated and improved, you understand, to reflect data consistent with the project final report."

"But you realize that he didn't and won't sign the final report," Dr. Merrell noted.

"No matter," said the voice on the telephone. "His signature is no longer relevant to this project anymore than he is. In a few months, Dr. Kelsey will be forgotten." There was a pause and then the telephone voice concluded before hanging up: "There seems to be nothing else for us to discuss at this time, Dr. Merrell. Thank you for your effort and hard work. Goodbye."

Dr. Merrell stood up and looked at the pictures on his credenza, the pictures hanging on the wall, the view of the sky out his picture window. It was that season of the year, that time of the month, when he could see the moon, faintly, even in the late afternoon. The moon was in its waning gibbous phase and Dr. Merrell could just see it through the clouds.

It was too bad about Frank Kelsey, he thought to himself. A very stubborn man. Dr. Merrell speculated that Frank's take-down would begin almost immediately. It was probably already underway. It wouldn't take too long and, once begun, it would be irreversible. Frank's existence would be sterilized. So, too, Earth's Moon. The sterilization of the frozen water in the Moon's craters would proceed posthaste, to undo an inadvertent contamination by Earth bacteria and viruses, so everyone had agreed. Once begun, it, too, would be irreversible. Project Jump the Moon would proceed. Life would go on. We live in a rules-based world. People like Frank... and me... just have to follow the rules.

Dr. Merrell decided to go home early.

* * *

Distantly, elsewhere, the voice that had been talking to Dr. Merrell on the secure back-line phone, was, meanwhile, talking with other people who were also distant and elsewhere.

Frank Kelsey was already off the agenda, already old news. Done and over. The topic for discussion was Dr. Merrell, his future usefulness to the project. The consensus was that Dr. Merrill, too, was disposable. Dr. Merrell's body language and sentiments hinted at less reliability than was desirable. Trees need to be pruned, shrubs need to be trimmed. No one is irreplaceable. Dr. Merrell, too, would need to be carefully watched and monitored. It was likely, just not yet, but one day soon, they concluded, that Dr. Merrell, too, would have to go. There were unwritten rules in the rules-based order. Sacrifices were necessary. The sacrifices of others. For the good of the order. Their good. And their order.

Author's Note

The names of the protagonists in this story are drawn from real people. "Frank Kelsey" is a fictionalized character whose name is derived from Frances Oldham Kelsey, MD, PhD.

In 1960, Frances Kelsey began to work in the pharmacology center of the Food & Drug Administration. One of the first drugs she was asked to approve for use in the United States was thalidomide, a drug manufactured by the German company Grünenthal that it marketed as a sedative, a flu medication and as a completely safe cure for morning sickness for pregnant women. William S. Merrell Co. - ergo the name Dr. William Merrell in the story - proposed to mass market thalidomide in the United States and reap enormous profit from its sales.

Thalidomide, however, can cause peripheral neuritis (damage to the nerves of the hands and feet). Crossing the placental barrier, it can result in birth defects like phocomelia, severe flipper-like deformations of the arms and legs, blindness, central brain damage, facial deformations and miscarriages. The pharmaceutical manufactures of thalidomide knew, or at least had hints, about the drug's problems and they deliberately chose to ignore them for the sake of making money. The pre-sale testing of thalidomide was limited, inadequate, and obfuscatory. It was a block-buster miracle drug, the companies proclaimed, the science be damned. If, later, there were occasional birth defects, who could actually prove the direct causal relationship between the drug and the defects?

Dr. Frances Kelsey, almost alone, sensed that something was wrong with thalidomide. She stood up to the enormous pressure heaped on her. Millions of doses of thalidomide were already being sold in Germany, in England, in Australia and elsewhere. The companies urgently wanted to sell to Americans what they had already sold to millions of expectant mothers across the globe. America was a lucrative market. Pregnant women were the marketing target. Only Dr. Kelsey held them back.

Dr. Frances Kelsey had seen indications in the non-U.S. medical literature that not all was well with thalidomide. There were medical anecdotes, a few limited observations, scattered reports of birth abnormalities and major health concerns raised by doctors in Germany, England and Australia. The reports were frightening. The damage to newborns appeared to be catastrophic. Dr. Kelsey dug in her heels. She demanded that the proponents, manufacturers and marketers of thalidomide prove that it was safe, that it did no fetal damage and that it did not cross the placental barrier; and she demanded that they establish its safety first before thalidomide would be allowed into the American marketplace. It is called the precautionary principle.

Doctors, pharmaceutical companies, politicians, lobbyists, everyone dumped on Dr. Kelsey for resisting the medical consensus that they claimed to represent. They ridiculed her. They derided her. They threatened her. They tried to go over her head. There was a lot of money at stake. The pressure was intense and unremitting.

Luckily - for the United States, at least - the information dam broke and the dirty secrets of thalidomide's legacy of death and birth defects came out before the Merrell corporation could break Dr. Frances Kelsey's resistance. Ultimately, thalidomide was not marketed in the United States. Lives were saved.

It isn't known exactly how many mothers and surviving babies were adversely affected by thalidomide in the countries where it had been marketed - possibly 10,000 to 20,000, likely more. Many additional thousands were stillborn or died soon after they were born.

When I lived in West Berlin, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, I lived very close to a German hospital that cared for survivors of the thalidomide disaster, babies who had been born without arms or legs or born with malformed feet and hands. I saw a few of the teenage survivors riding the public buses to the hospital, holding their schoolbags at their shoulders for want of any arms, or using elaborate walking devices for want of any legs. It made a lasting impression on me, of their courage, and of the courage of Dr. Frances Kelsey who saved countless thousands from a similar fate.

Dr. Frances Kelsey died in 2015. She was 101 years old.

She was a heroine and the epitome of courage.

____

Note 1: Top photo credit - Diatoms living between crystals of annual sea ice in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. Image digitized from original 35mm Ektachrome slide. Prof. Gordon T. Taylor, Stony Brook University Public Domain File: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diatoms_through_the_microscope.jpg Created: 1 January 1983

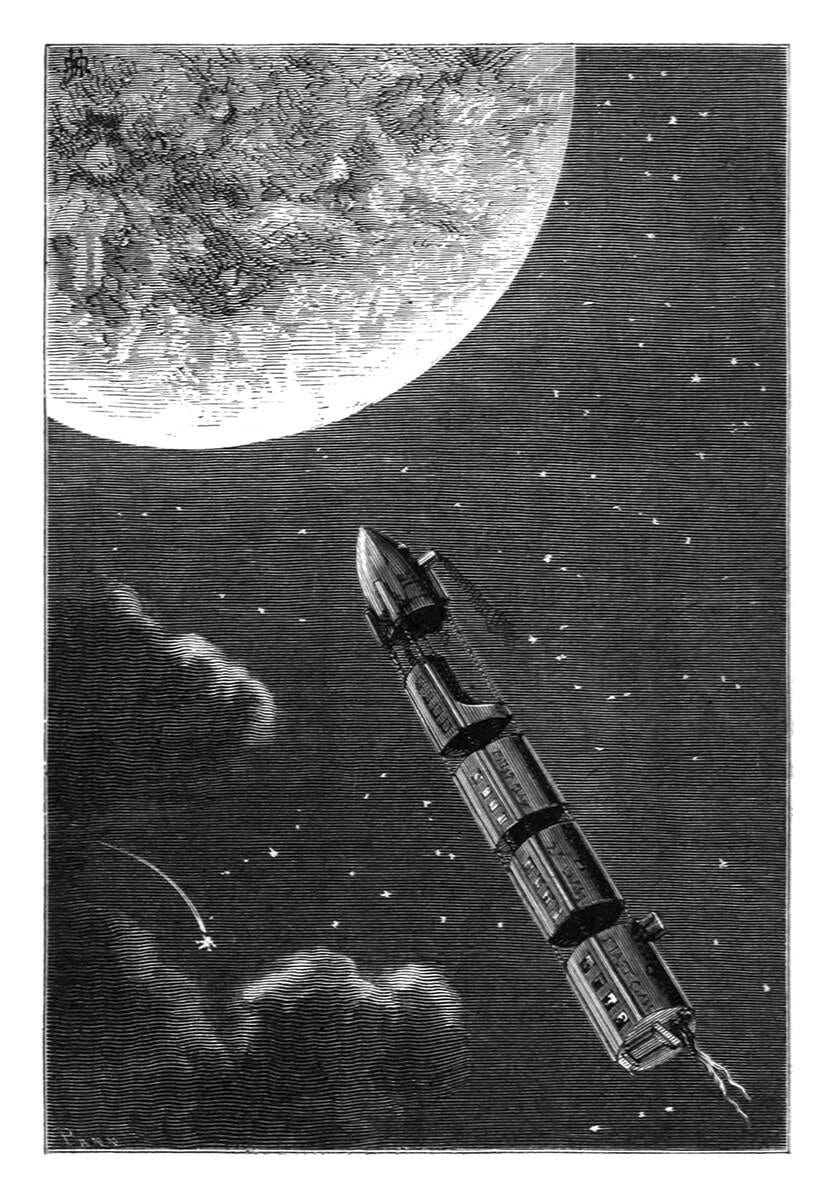

Note 2: End art credit - Projectile Trains for the Moon | Les trains de projectiles pour la lune.url=https://www.oldbookillustrations.com/illustrations/trains-to-moon/ | author=Montaut, Henri de | year=n.d. | publisher=Old Book Illustrations. Appeared in Book Title: De la terre à la lune Author: Verne, Jules Publisher: Paris: Hetzel, n.d.