The GPT Chat-bot Lawyer

"Art" Imitates Life

I have been inundated by a tsunami of spam from law firm tech "consultants" offering to help me ramp up my law practice. They offer me subscriptions to "AI generative pre-trained law-transformer services." I can rake in the dough, they tell me! Artificially intelligent chat-bots will "interview" prospective clients, write up innovative pleadings, research the law and draft briefs comme il faut in support of motions to the court. I understand how generative pre-trained transformers work so I am certain that their pleadings will be nothing less than "innovative."

Artificial intelligence sells these days. It's the "Next Big Thing."

Once it was Segway's self-balancing scooters, artisan cupcakes, and pet rocks. Today, self-driving autonomous electric vehicles promise to drive you anywhere with no one in the cockpit... provided that there are no obstacles in their paths, no other cars on the road, no pedestrians, no skateboarders darting across the street, no bicyclists, no detours, no cross-walks, no traffic jams, no dogs (or chickens) crossing the road, no fire trucks or police cars, no construction equipment, no soccer balls kicked into the street, no traffic cones, no wet roads, no snow... and no lawyers to sue for the inevitable catastrophic accidents.

You have to break a few eggs to make an omelet, the self-driven promoters argue. Well and good, so long as you aren't the one whose eggs get broken.

A current story regarding generative pre-trained transformers relates the saga of one New York lawyer trying, and failing, to pass off GPT briefing in a court of law.

His legal brief submitted to the court read fluidly, persuasively, intelligently. But, oh woe, it was pure hooey. The brief was full of false citations, concocted quotations and made up authorities. An AI law-bot had selected, rearranged and transformed what it had harvested from the Web into something that sounded convincing, but which, in reality, was based on the utterly impostrous. But, but, but... the New York lawyer assured the Court after the fact, he had queried the law-bot whether its authorities were true. It replied, apparently with a straight AI face, that they were true. Rather like today's news reporters. And our culture. And our politicians. And the economy.

We live in an age of deception and falsehood. Every leader in every segment of society has mastered the art of artfulness. More than 50 years ago, Marshall McLuhan wrote that "the medium is the message." Today, the narrative is the message, the "medium" is digital and substance barely ranks. We're all about the candy wrapper. Whether there is any candy inside the wrapper is immaterial.

Comedian George Burns once quipped: "Sincerity is everything. If you can learn how to fake it, you've got it made." But lawyers faking the law? Give me a break!

Can it be that what we thought was a temple of truth and justice, turns out, in reality, to be just another castle made of sand? Alas, too often in the courts of law, just as in life outside the courts, it really is just a shifting pile of sand. Or a candy wrapper.

Consider the New York lawyer who GPT-ed himself in flagrante delicto. As the stories intimate, his local bar association may yet punch the gentleman's ticket to practice law for allowing a robot to litigate under his imprimatur. It is likely that if there was one attempt at barristerial deception like that one, then there must have been other lawyers, too, who have tried. And, no doubt, there are those who have succeeded. It begs a question at the core of the judicial system: exactly where is "the law" that the system relies on and who vouches for its authenticity?

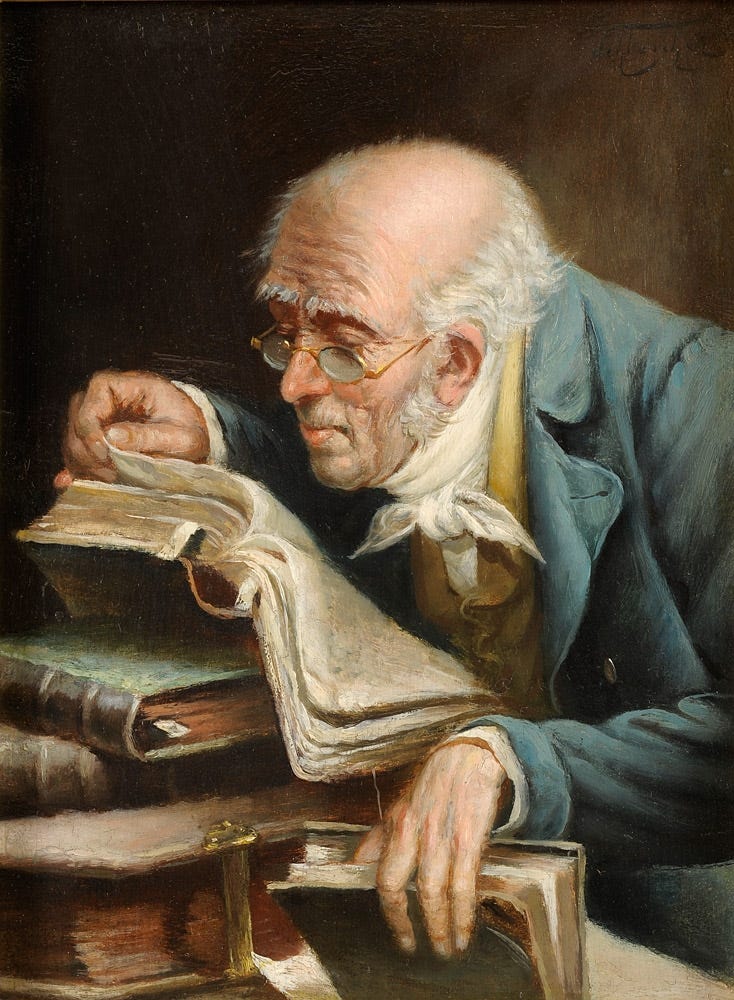

Clearly, lawyers and judges cite to statutes, cases and precedents to frame their clients' cases. But who verifies any of the statutes, cases and precedents? At one time, a judge's law clerk (or several law clerks, if the judge were sufficiently high up the judicial pyramid) would be tasked with the sometimes numbing job of verifying the citations and reading the cases relied on. At one time, there were libraries that contained hard copies which may or may not have accurately recorded a law or a decision. But there they were and they were difficult to alter without wholesale book-burning. What you read today (absent book-burning) could be read tomorrow.

Today, the libraries still exist, but sometimes as little more than de facto homeless shelters. Once upon a time, official reports were studied in the carrels among the stacks of books. Law clerks (and sometimes judges) earmarked them, piled them up on desks, photocopied them, high-lighted the copies, cross-checked and authenticated them. Today, legal research consists mostly of searching the data banks... much like an artificially intelligent generative transformer would do.

For nearly 50 years, what has passed for "legal research" was computers rummaging through digital archives, now mostly residing in for-profit corporate server farms. Almost every attorney and judge in the United States does "research" on line by searching for key phrases in the statutes and the published opinions, all located in the privately owned and operated "Cloud." All that GPT does is to allow greater range in the key phrases so that they almost resemble everyday “natural language” queries. With multiple queries and answers, the exchanges may seem like consultation. GPT itself does not perform the searches, although the tech oligopoly has begun deploying GPT into search. Hence the same core question remains: does anyone know whether what the digital search turns up is accurate or complete? Digital book-burning, by the way, is fast, easy and doesn't make any flame or smoke. Data can be, and certainly has been, "rearranged," deleted, edited, revised and transformed. Who would be the wiser?

What happens if a court relies on a bogus GPT brief citing bogus legal authorities, and this court then issues rulings that then become opinions of record that are then cited as authority for subsequent opinions of record? Theoretically, the "bad decisions" can later be corrected or overruled. But this will happen only if other courts are paying attention. Is anyone actually paying attention? Additionally, corrections will happen only if other courts are not also relying on bogus briefs and concocted authorities. In that regard, think about how the US State Department, the Department of Justice and various security and intelligence agencies function.

False briefs and authorities can get piled on top of other false briefs and authorities. Like the cosmological explanation of the universe as turtles standing on the shells of other turtles in an infinite regression, the legal cosmos could be just bogus legal authorities stacked on top of other bogus authorities, all the way up and all the way down. Who is to know if or when, eventually, as a matter of precedence, the ludicrous becomes Law?

This seems abstract, but it is not.

For centuries and centuries, Neoplatonism trumped experimental science.

The world was flat.

Blood-letting and trepanning were the doctors' treatments of choice.

Planet Earth was the center of the universe.

Bathing was bad for your health.

Phrenology told the story of your life by the bumps on your head.

Kings ruled by Divine Right.

Miasma caused the plague.

The universe began 5,000 years ago.

Hieromancy explained how chopped chicken livers could foretell the future.

Dinosaurs and humans lived side-by-side.

Tulip bulbs were an investment.

Lone gunmen shot JFK, RFK and MLK.

Iraq's Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction.

Those accused of crime were tortured and tried by ordeal.

Witches and heretics were burned.

Supposed revealed truths have a way of unraveling. But sometimes even the most preposterous untruth retains currency even after it has unraveled.

I am writing from 44 years of legal experience. I personally have encountered cases of record where judges have simply misstated the law, misunderstood the facts or completely gone off the rails pursuing their own agenda. If I have experienced this a few times over the years, then so must others.

In Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan, he postulated a society whose denizens voluntarily yield sovereignty to the State in exchange for order, truth and justice. In the absence of this 'civilized' agreement, Hobbes famously wrote, life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short." Among the benefits that such a state would confer on its subjects as the quid pro quo for their submission, are those taken for granted, but absolutely essential to civilized life: a stable, dependable and fair economy; government you can trust; honesty rewarded, criminality punished; a just, expeditious, intelligible, rational legal system; a society where the candy is sweet and the wrapper is dross.

A legitimate, affordable, dependable, and effective system of law is part of the Hobbesian social contract. That means a legal system where the results are both predictable and perceived to be fair. That is the essence of the legal concept of stare decisis - that past decisions lay down principles that, predictably, will be followed in similar circumstances in the future. That is why lawyers and judges cite to prior cases. That is why the New York lawyer's GPT'ed brief quoted other case authorities, albethey pure fudge.

Stare decisis, however, applies mostly to the lower courts. The higher one rises in any legal hierarchy, the more stare decisis becomes a prop for just making policy. By the time one gets to the highest court in any legal system (the courts that have the ultimate power to create or discard "precedence"), the citation to precedential authorities becomes just candy wrapper again. They are cited (in or out of context) to make the policy result that the highest court wishes to achieve seem to be a natural extension of precedent.

In theory, the case precedents ought to just buttress the independent argument that is logical, fair and just. In theory, stare decisis is not the argument itself, but supports it by dint of prior similar decisions. In theory, a brief submitted by a lawyer - or written by a generative pre-trained transformer program - should be persuasive if the arguments are true, regardless whether there are case law antecedents.

Thus, the anecdote about a lawyer using GPT to write a brief focuses on the secondary issue of citing non-extant authorities. The primary issue is, was the law-bot right? The AI law-bot might have ginned up its authorities, in which case it was practicing law by deception. Real lawyers are not ethically permitted to deceive the courts (although, it might not surprise you, they do it all the time).

But what of the arguments made by the AI law-bot? Regardless of the false citations, did the arguments themselves make sense? Were they supported by the facts? Were they persuasive? If the answer is 'yes' to all three questions, then we have a genuine advance in artificial intelligence. The Law, at its core, should make sense. Let mere humans find the 'authorities' that support the persuasive argument.

If, on the other hand, the AI law-bot's arguments were as nonsensical as its case citations, then art(ificial intelligence) is imitating real life. Give that GPT law-bot a license to practice.

Print its law license on a candy wrapper.

Note 1: Mid-article painting by Carl Schleicher Der Bücherwurm, Created: 19th century (precise date unknown), Public Domain